ALTERPIECES

EVEN AFTER WE DIE,

THOUGHTS BITE US.

Sculpture in present-day Cuba is not the same as it was two decades ago. The discipline began a process of substantial transformation in our culture in the 1980s. It is no longer a question of following representative, generic, symbolic or syncretistic criteria to create works with internal and external meaning, but to produce art that dialogues with space and makes it part of the work itself, assuming the inter-generic possibilities of extra-artistic resources or even using proxemics or adopting the logic of spectacle. The virtual and sometimes renovated concept of sculpture that has not died –because things in art come to stay– serves as a reference point in spite of the existence of variants that occasionally seem to distance themselves from a more generalized approach to this discipline. In fact, sculptors of such works become different kinds of professionals in need of a superior visual and conceptual culture, not infrequently influenced by the fields of design, industry, handicrafts and art. That time marked the beginning of a sculpture of symbiotic change which needed to be seen from a distance and required public acceptance and a different kind of critical evaluation.

San Juan came onto the scene as a sculptor in the vortex of this dynamic of change. Not surprisingly, change has been the only constant in his work. We should not be surprised by the range that his work has covered in just a few short years. Constant change is a sign of artistic searching born from creative dissatisfaction. A profession that is parallel to that of sculptor –set designer– has allowed him to penetrate the demons of design, painting, stage, and the expressiveness of the human body. A profession, in the end, has given him recognition in that field of theater, leading him, with an enriched vision, to question the preliminary period of his own career as a sculptor: when he thought he could transmit his aesthetic interests of a sensual, environmental social and even erotic nature through works that showed elements of hybridity and subversions of the conventional portrayal of the human figure, San Juan experienced what Lezama Lima calls «an unexpected» –a sudden instance of change that altered his artistic path.

Sculpture as a work propelled by contact with dancers’ bodies, the theatrical set as a space of imagination projected to works of sculpture: such are the complimentary pathways that rule a good part of the work of this unique artist. His creations almost always have a kinship with environment, installation, participatory and performance art, yet they also work on the level of ceramic sculpture, not only for understandable reasons of survival but because they addresses expressive issues of form, finish, symbolization, textures and tones while providing an artistic alternative useful for larger projects.

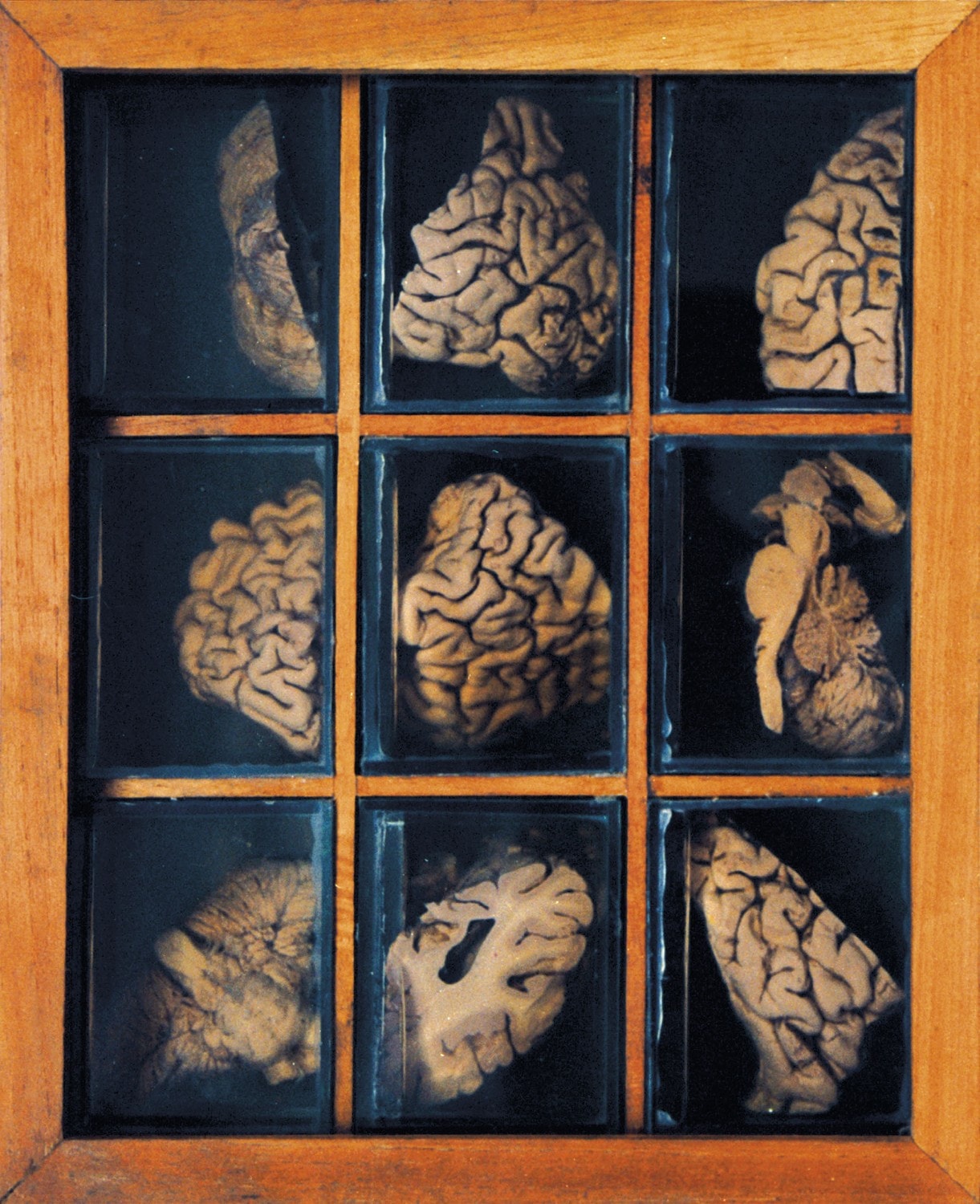

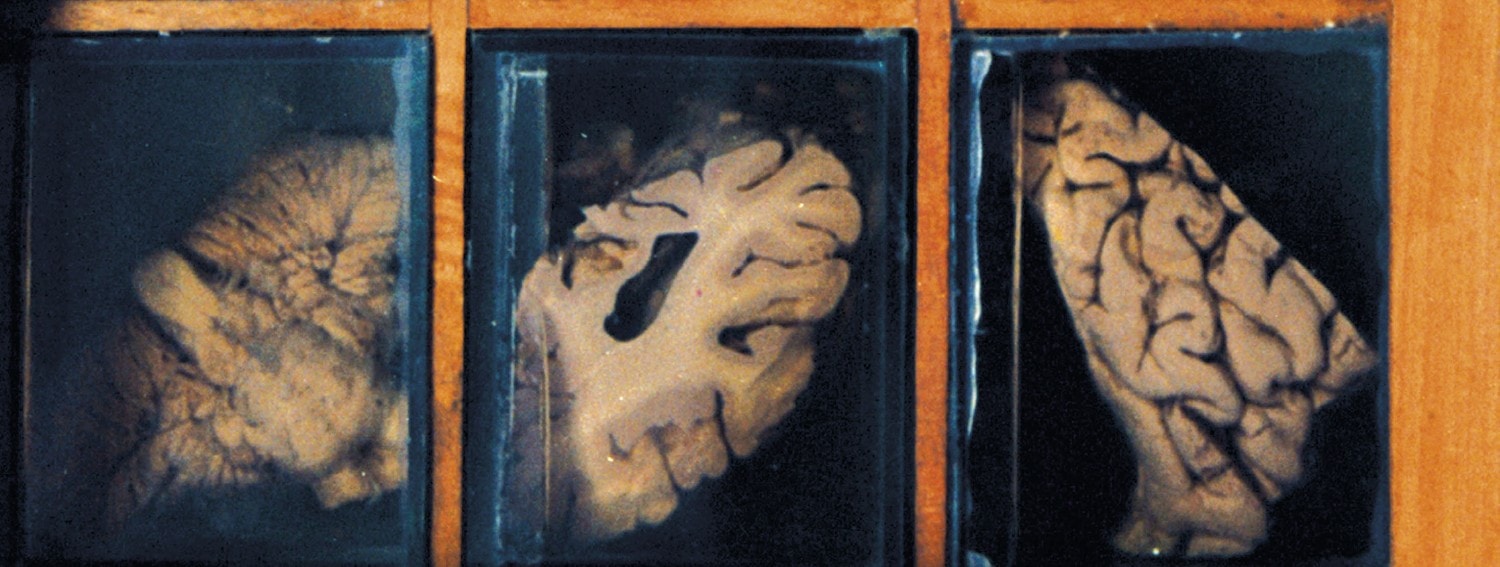

San Juan knows that the human body, both in its entirety and in pieces, is a prodigious sculptural creation in its own right. All manner of hands, eyes, faces, tongues, hearts, and extremities obtained from the dissection of corpses, become –by the transformative work and grace of this artist– material resources, forms and mathematical symbols that separate reality from fiction, the carnal or anthropomorphic ingredient and the post-figuration artistic materials that, whether presented in a static or performance context, seem to echo Sartre’s assertion that «we are within language as within our body».

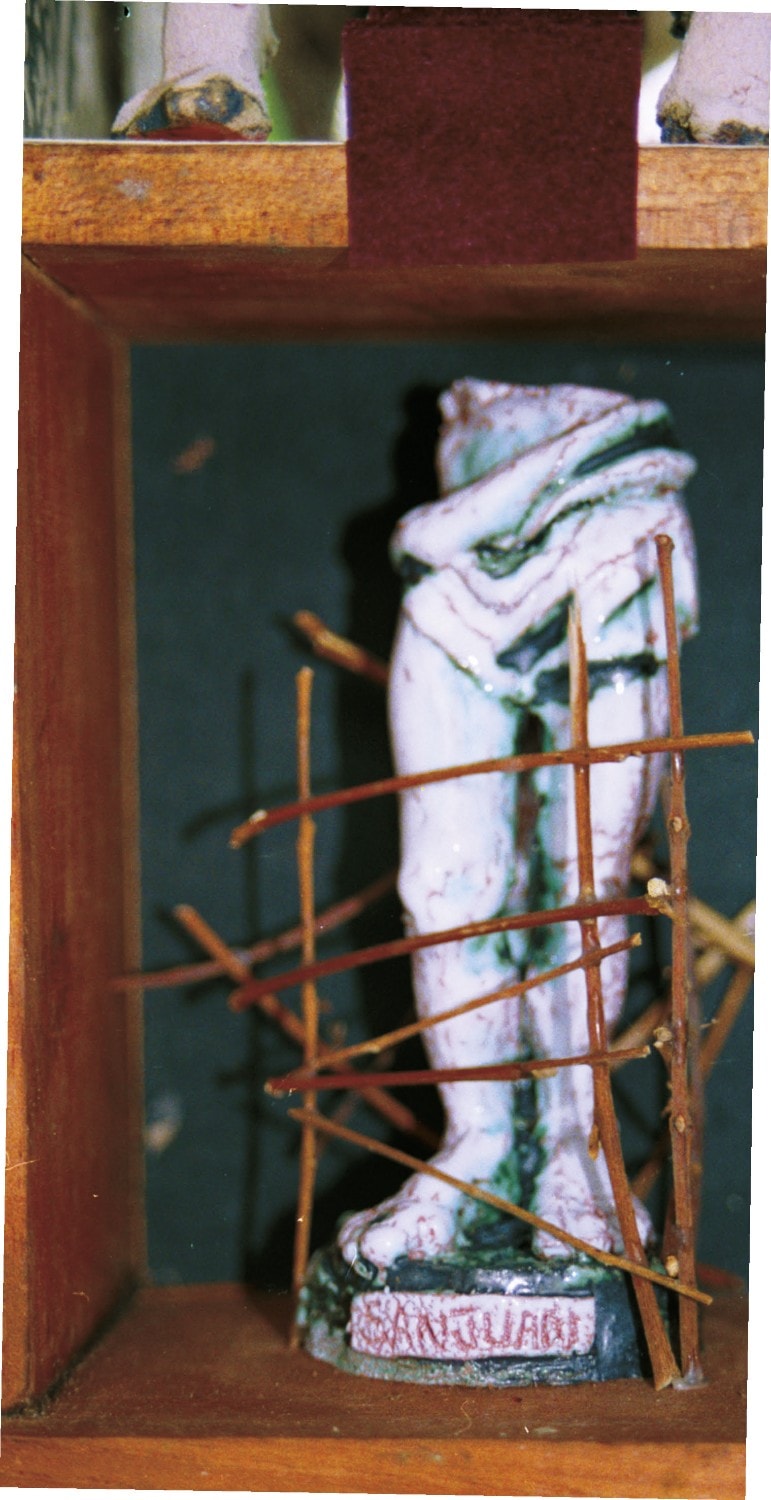

While other sculptors may prefer harmonious proportional balance, San Juan frequently chooses the opposite: torsos and bodily representations where human vision is stated from an inharmonious expressionist and sensationalist perspective whose significant features include a lighthearted gesture of the ugly, the grotesque, in addition to the formal exaggeration of the lower extremities and other anatomy, adding a level of drama and absurdity which is essential to his work. Juxtaposed with work featuring the human body as somewhat ornamental and poetic

ceramic pieces that, depending on their function, are evocative of that which is beautiful, altered, injured or redefined by metal objects embedded in the chest, reminiscent of St. Sebastian shot through with arrows. This sculptor adopts a pendulous and oscillating perspective that can take different yet complementary routes and leave an artistic representation of the contrasts created by the stage and its time and sense of reality.

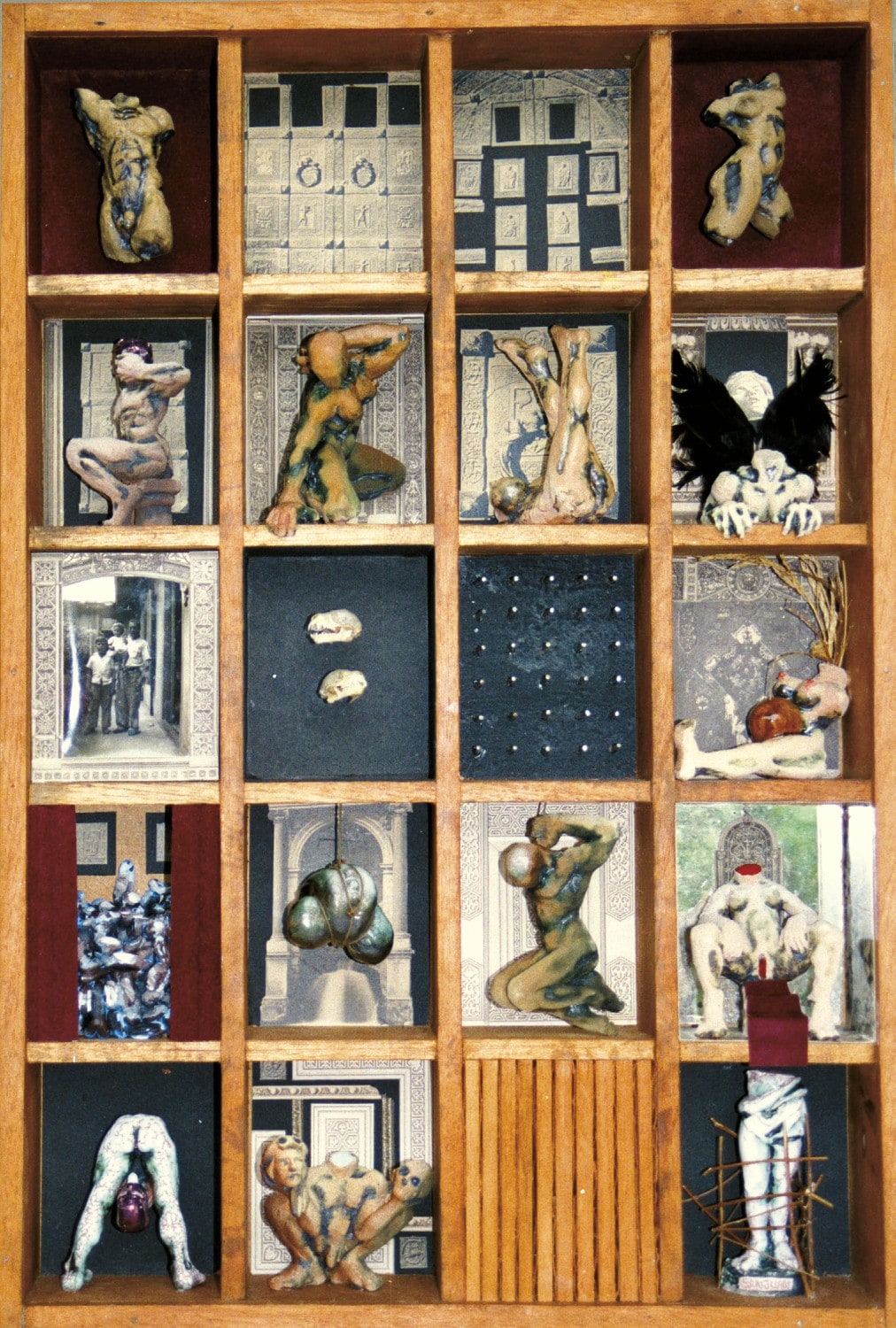

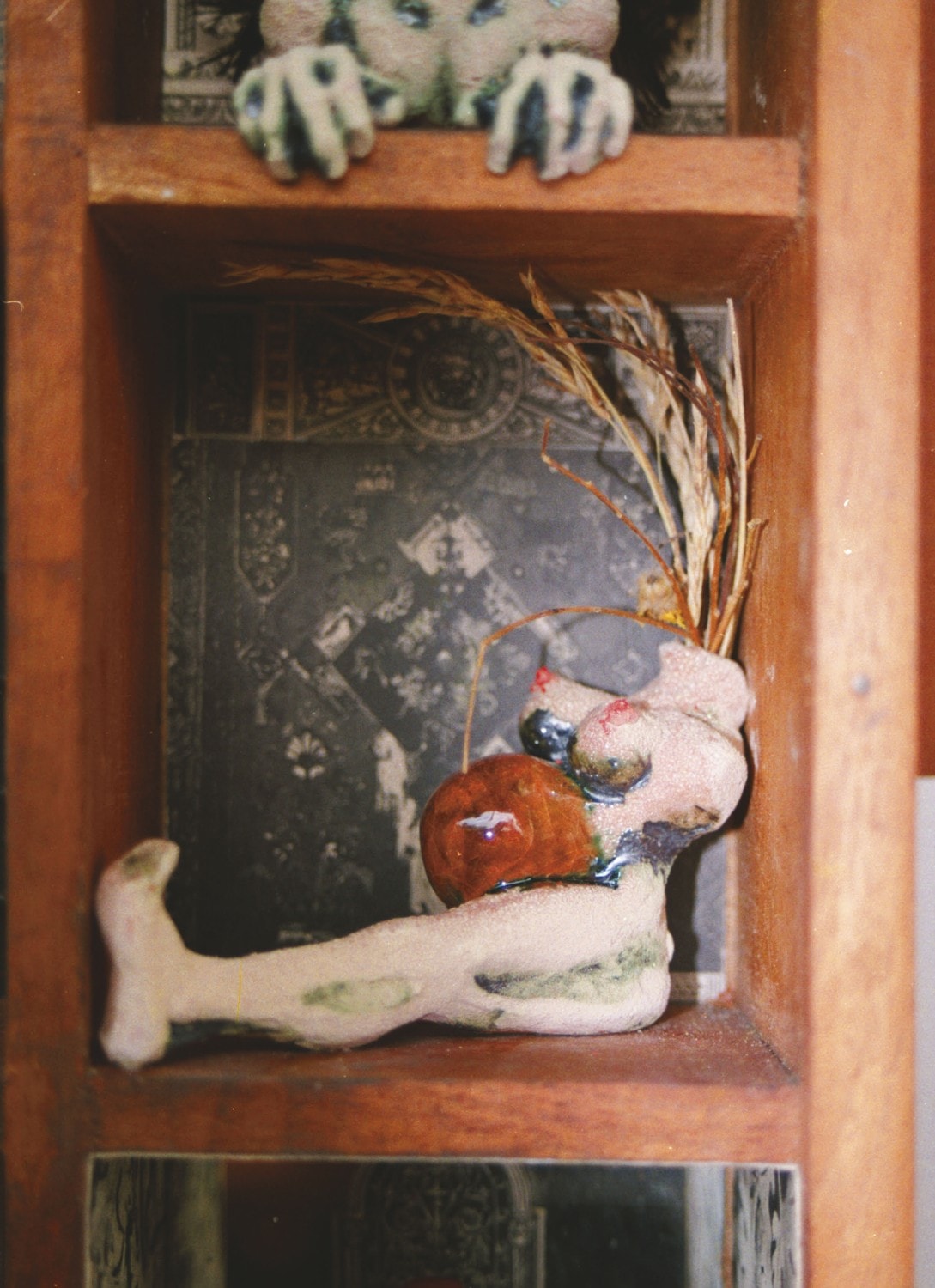

His first efforts included an altarpiece with small sculptures, photographs and dissimilar formal elements with an evident stage design influence, mostly characterized by an expressiveness which rejects the formal and «serious» canons of salon sculpture. This work marked the beginning of a journey that would bring together autobiographical data, social experiences, pleasant sensations, love and the decision to face the challenges of an art form that would make the human body its main conduit.

Without any anti-figurative, anti-classical or anti-anthropocentric prejudices –now commonplace in the artistic conscience of young Cubans– Rafael once again opted for a style with a long history in the art world. It began to take shape in the processes of modeling, casting and sometimes forging –a complex of perceptions and symbols inspired by situations of everyday life and the theater stage. Fortunately, his imagination had never overpowered the crafts of sculpting and set designing; both functioned in unison regardless of the concept, as a reservoir of techniques and procedures or as a way of designing that nurtured his craft or provided a synthesis of contemporary urban reality. From that creative perspective his dancers, gesticulating figures, huge effigies supplemented by natural human organs and extremities, his peculiar representations of the Venus de Milo dismembered by present-day existential drama, become, not only part of exempt sculptures, but also center of a space of meaning, often expanded by other complementary elements, capable of becoming fields of physical, performance action, based on the evoking visual nature of dancing.

Anyone looking at the same time at stage designs and sculptures by Rafael San Juan will discover that the former inspire the spectacular dialogue that is proper of sculpture, while the latter attempt to embed into the physical dimensions of the work for a salon or into the model for hypothetical monumental commissions a varied number of motivations, where the «fetishistic image», the critical idea and the organic structures unleash sensorial and conceptual expressions. Each of his works involves explorations of material themes and a search for new styles of artistic and inter-genre communication. For him, sculpting becomes a point of convergence of ceramics, dance, myth, puppetry, tragedy and comedy, carnal love, and gestures associated

with situations that reveal typologies and situations torn from society. For this reason it is normal to perceive in his works the effects of the «Apollonian» or «Dionysian» nature of the angels, proper of the harmonious forms, and of the demons of the oneiric overflow.

* Manzanillo, 1947

Visual artist, art critic and essayist on cultural themes. Guy Pérez Cisneros Prize in Critique for the work of a lifetime.