ART

AND LIFE

WHOEVER FIXES HIS GLANCE

IN SMALL DETAILS

WILL BE CAPABLE OF UNDERSTANDING

THE IMMENSITY OF THINGS.

It´s only art

At the dawn of the second decade of the 21st century, discussions about art –whether traditional, conceptual or contemporary– range from truces to culminating points, but in countries like Mexico they sometimes reach bellicose proportions in the pages of magazines and cultural supplements. Mexican musician and artist Miguel Calderón told a magazine: «I stopped making art a long time ago because from one day to another everyone became an artist» [Código 06140, no. 32]. Critics and radical artists of different stripes dismiss the artistic merits of their fellow combatants and singularize themselves as the pure, true artists: the rest are charlatans, impostors, merchants. Meanwhile, the powerful and influential art market stands smiling and welcomes all, acquiescing to each one in accordance with current demands and fashion, even if it is all a farce. In the borders, artists unconcerned about passing trends dedicate themselves to their vital, essential projects. They nourish from fundamental aspects of the history of art and take from each period or style what best suits their artistic needs and their own time, without conflicts or false dilemmas. They are complete artists who embody a modern Renaissance. fluent in old drawing, painting and sculpture techniques, they also have become experts in media and new technologies. for these artists, art is inseparable from life, and a life connected to art is a full life –not necessarily a happy or pleasant one, because those who know and feel more may despair more of the human condition, or even of their own.

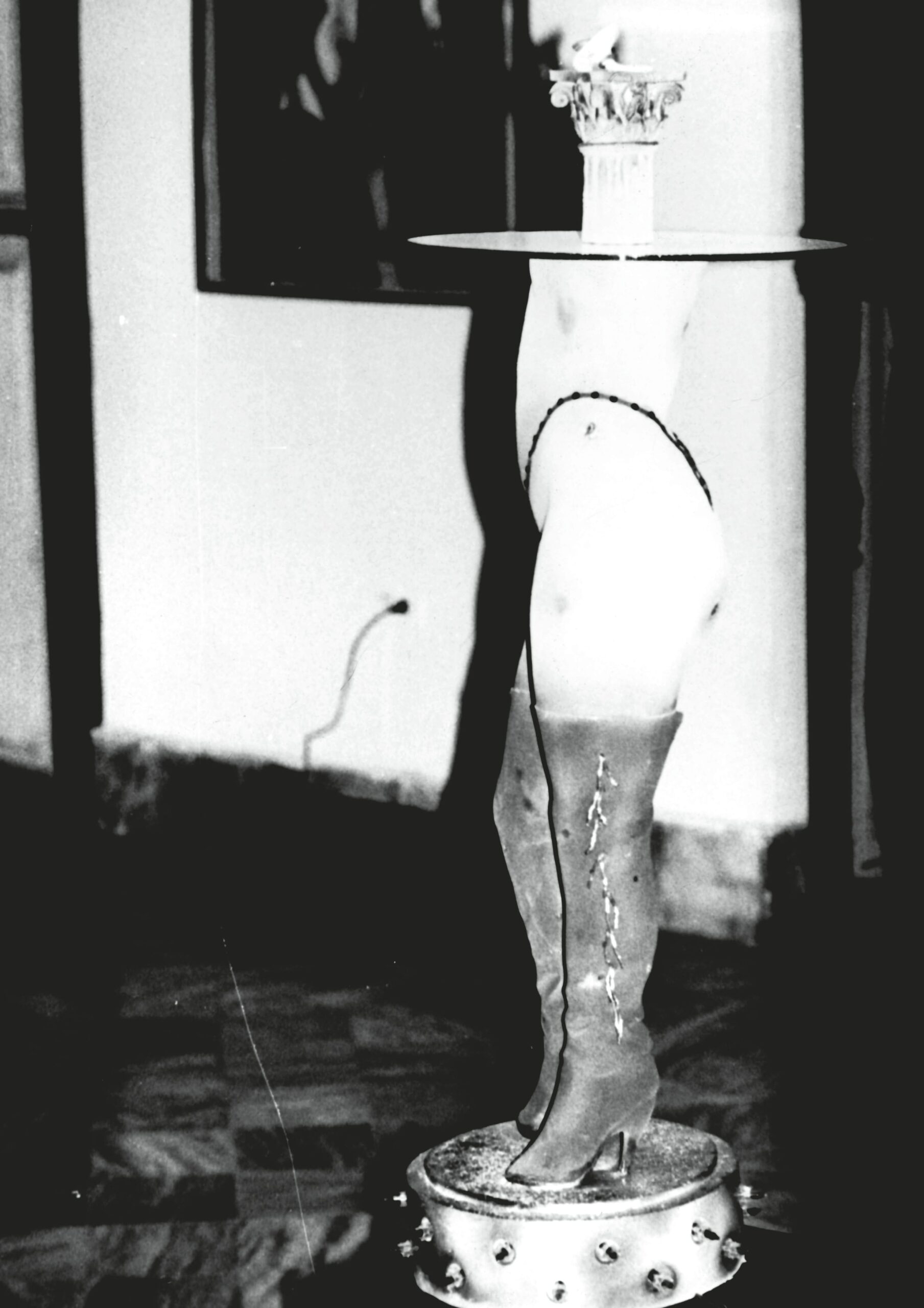

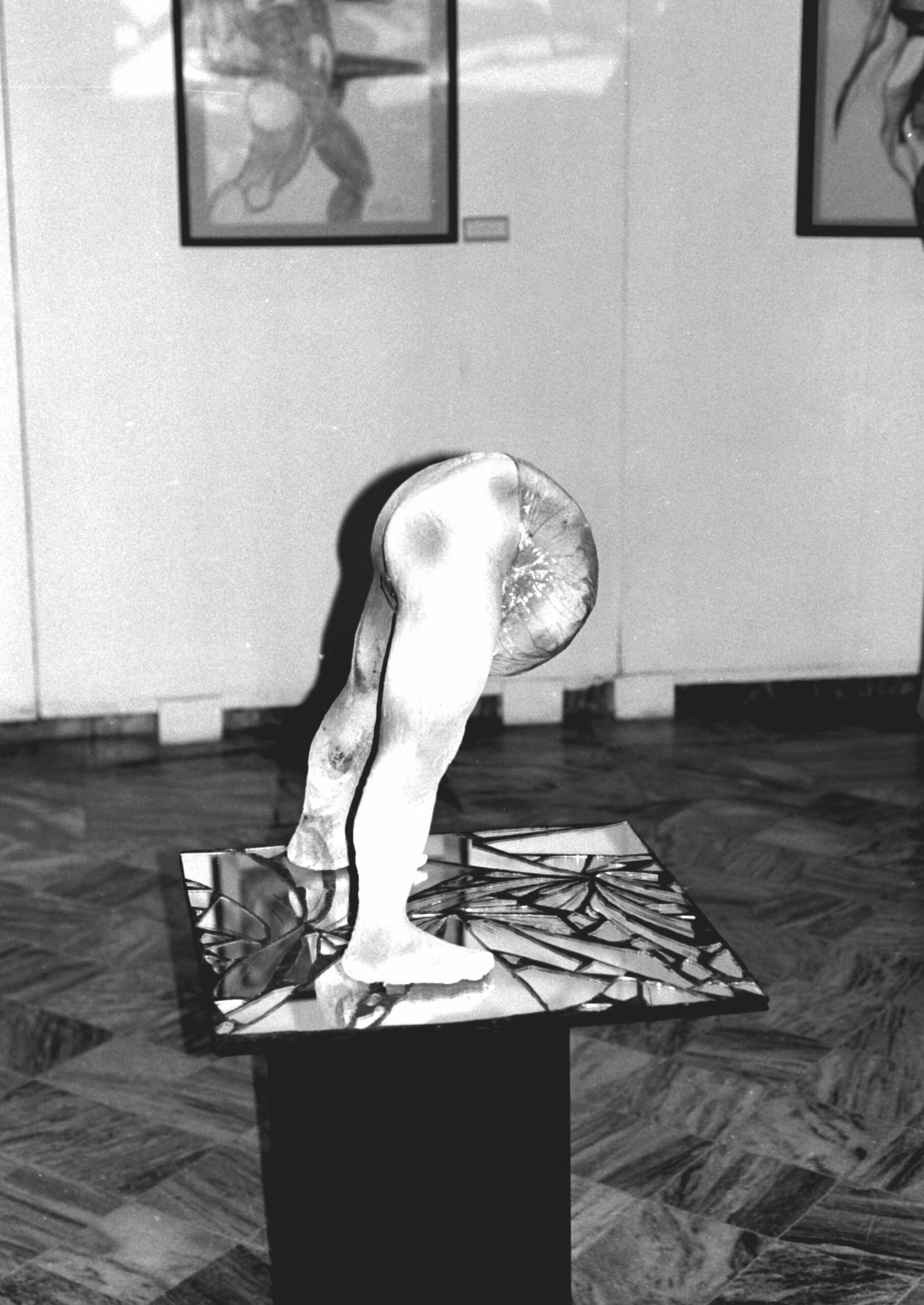

from life comes art, and art in turn feeds life, enriching it in sometimes unexpected ways. This is why art should not be limited to the confines of galleries and museums. why not appreciate it, say, in a forest or on a bus? yes, there is art in parks, gardens and streets, but not always the best or enough to transform the lives of people or straighten the wobbly course of the world even just a little. These ideas come and go as I examine works –many uncompleted– in the studio of Rafael San Juan, an artist capable of risking everything if he believes a project is worth dedicating himself to, and who does not necessarily abide by the rule that a work of art needs to be eternal; that is why some of his ephemeral pieces include parts of human bodies such as arms, hands, viscera, brains and even a fetus like the one sleeping in the open womb of a huge clay mother with a loving virginal face

(Sentimientos ocultos, from the Hueco y Muscular series, 2002).

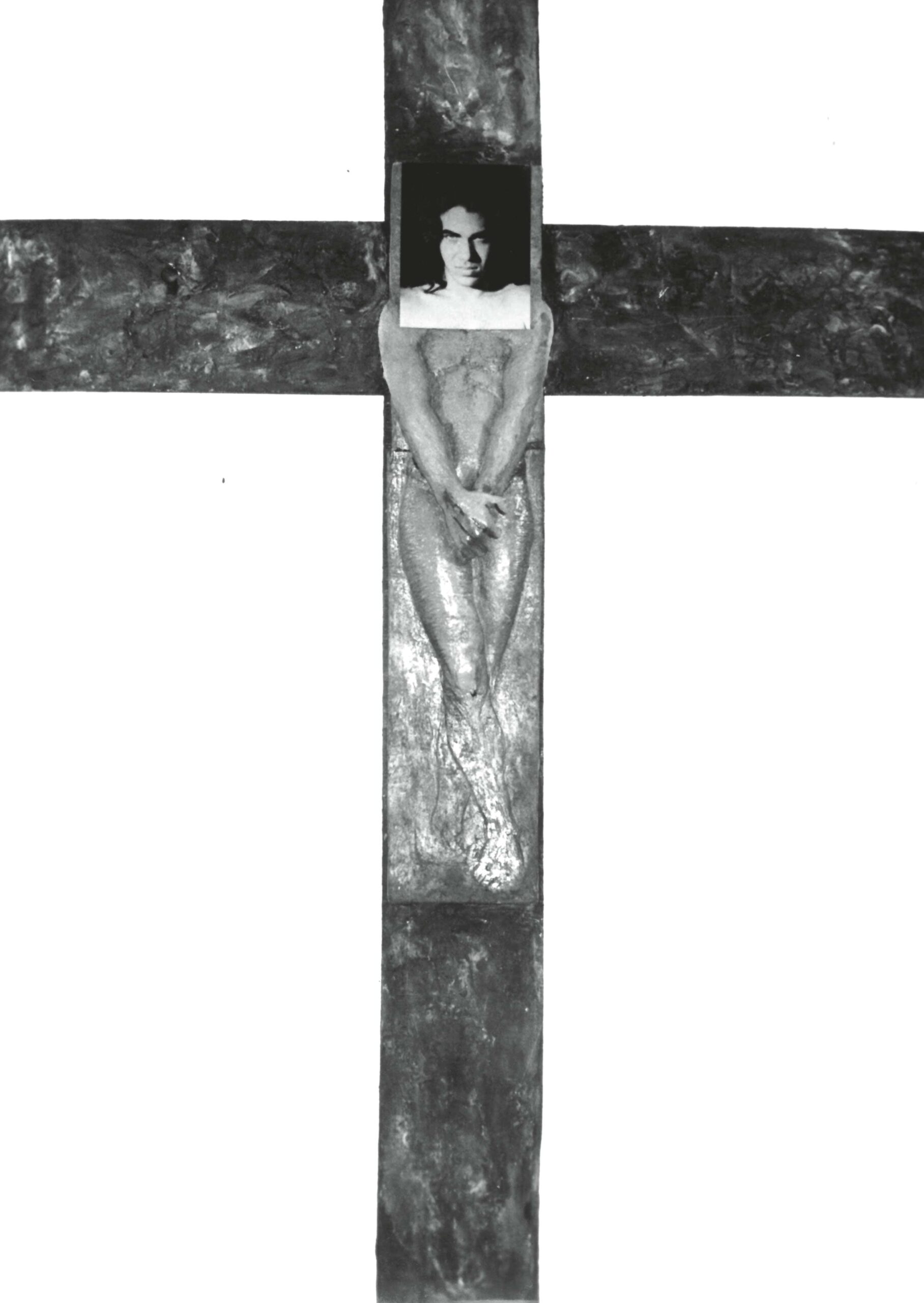

Artists’ studios and workshops are filled with marvels in gestation waiting to emerge one day as finished works. The studio of Rafael San Juan also harbors mysteries that seem to hide from the gaze of the curious. On its walls, among many others, hang two large works which warily depict hands perfectly drawn in pencil, as well as three-dimensional elements, metals and rope. I wonder if any of our «conceptual artists» would be able to draw with such skill, or have the guts to come up with a piece which I saw in a folder of previous work depicting a Christ modestly covering his genitals.

Art has been an inseparable part of San Juan’s life from the time he was a boy, when he fashioned his own toys from wood, clay or plasticine: warships, dinosaurs and any kind of real or fantastic beast «Put them in the freezer to harden», a great aunt advised him. he would engross himself in games that lasted all afternoon in the old family house in a central district of havana, where he was born in 1973. Little could he have imagined that years later he would create with his hands that giant wooden fish hanging in an art gallery, a stunning piece from his still unfinished Éxodo series, which has allowed him to explore the possibilities of materials as different from each other as fiber, jute, and clay to build giant wings, hands and hearts, such as the five from the Sístole perpetua series that floated, imposing and silent, in the space of the San Pancho Cultural Center during the I Symposium on Monumental Sculpture.

There was an art school near his house, but his parents enrolled him in a normal school. Of course, a few years later he realized that it would have been good to have studied there, but neither his mother, a civil servant, nor his father, a military that had fought in the Sierra Maestra mountains with fidel Castro –and was almost never at home– would have ever entertained such an outlandish idea. In the end it did not matter much, because his restless teenage spirit absorbed everything in view. he was fascinated with history museums, biology and aquariums, where he spent countless hours observing the strange shapes and exotic colors of the creatures swimming in them… having considered studying for a degree in biology, the last thing he imagined at that time was that he would soon invest all of his curiosity, knowledge and skills in a noble and generous profession, full of both satisfactions and displeasures.

The Errant Cuban

Like many Cuban families, the family of Rafael San Juan split up after the Revolution. Many were able to leave the island, and many more were left to face the difficult circumstances that the new revolutionary government would find itself immersed in. Rationing, shortages, military service and a thousand other problems were the hostile scenario under which Cubans would have to live, work and study, regardless of whether they agreed with the new regime or not.

During the trips I made to havana in 1981 and 1984 –the first at the invitation of the National Union of Cuban writers and Artists (UNEAC), and the second to attend the II Latin American Symposium on Photography–, I met artists like Raúl Martinez (1927-1995), who introduced pop art to Cuba, the playwright Abelardo Estorino (1925) and photographer Alberto korda (1928-2001), who took the famous photo of Che Guevara. I also got to know the most important and decisive generation of Cuban artists since the 1960s, which revolutionized contemporary art not only in the island, but around the world, with bold and unique works that combined traditional art with the latest international trends, and incorporated into them the cosmogony of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, Afro-Cuban Santeria, hyperrealism, intimate and experimental photography as well as installation and performance art. Many of these artists –who were restless, enthusiastic and impassioned– were sponsored by prestigious galleries in Mexico, the United States and Europe, and began to gain international recognition at major biennials and art fairs. Cuban critics and curators also began to enjoy success abroad. In the 1980s and for part of the 1990s it seemed that nothing important was happening in Cuba in the art sphere and that all Cuban art was being produced (or reproduced) beyond its shores. what was certain was that a new generation of artists was coming of age in Cuba, especially in havana.

The Academy

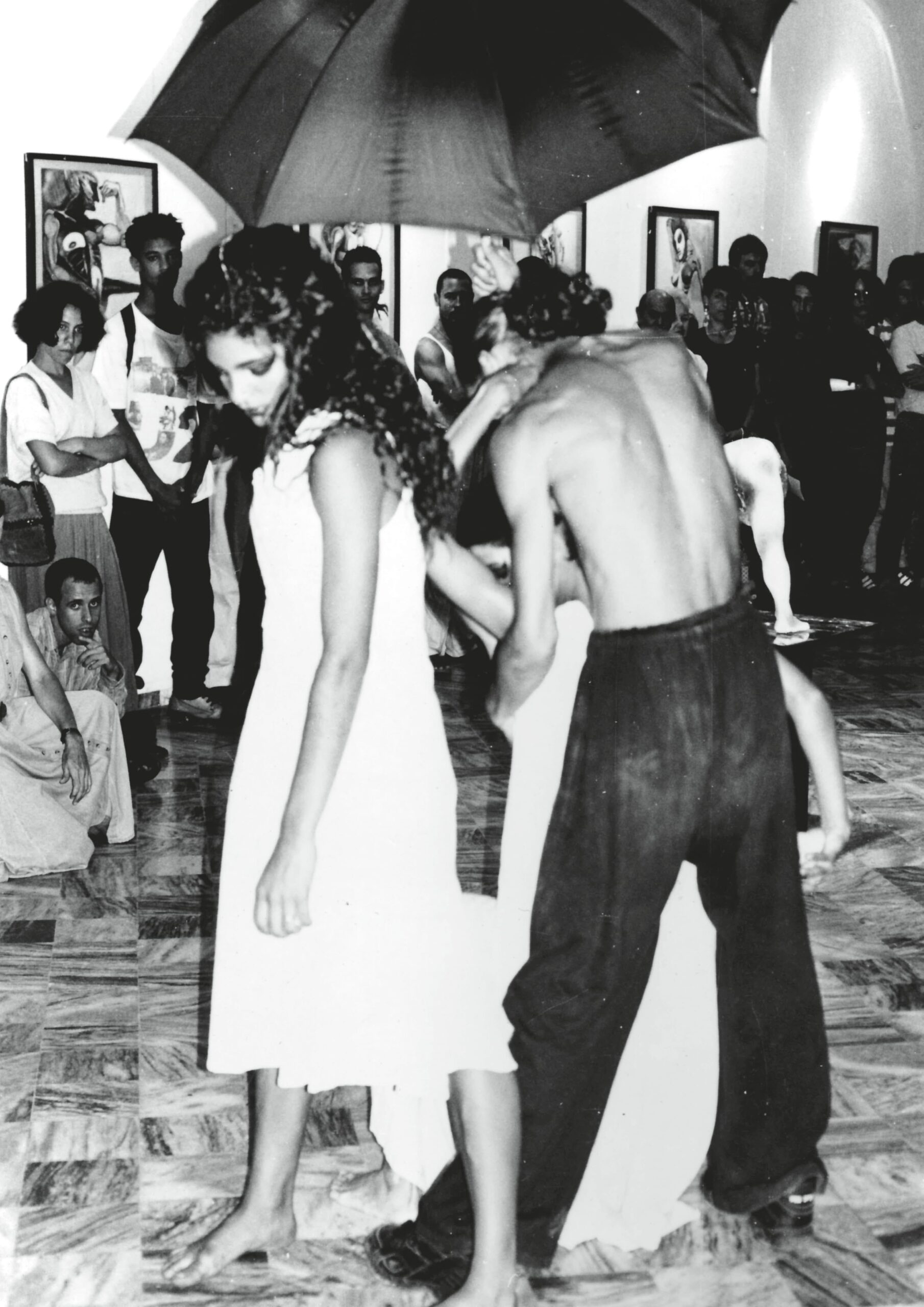

San Juan became increasingly enchanted with the wonders of life and the mysteries of death, and he seemed destined to study biology. A cousin who lived very close to him, a biologist by profession but also a lover of culture, introduced him to the world of books, music and art. his cousin took him to meet the famous artist Servando Cabrera (1923- 1981), and around that time he also met Alfredo Sosabravo (1930). Visits to these and other artists made the adolescent San Juan envision his own future as an artist who would discover and create worlds that were just as passionate as theirs. he began to take classes at San Alejandro Academy of fine Arts –the old school, somewhat neglected, where he developed and perfected his skills in drawing, painting and modeling– and at the higher Institute of Art (ISA) in havana, where he first started to learn about performing arts and work with theater and dance companies. Although studying at ISA had its ups and downs, San Juan gained a solid theoretical and practical foundation through considerable effort that included many kilometers of cycling under the scorching tropical sun.

The teaching of art and its techniques is essential, says San Juan, who also took it upon himself to learn the techniques necessary to work with and master such diverse materials as steel, bronze, clay and wood. from a drawer in his studio he takes out an old and useful book which he occasionally consults, entitled, Gran recetario práctico para el ingeniero operario y el industrial (Great Practical Recipe Book for the Operational Engineer) by w.w. Parker (Buenos Aires: Glem, 1944). To build a six-meter sculpture, one must carry out calculations to know the strength of materials and also have a bag of clever tricks for things such as making a clay man breathe using a humidifier. Long stretches spent in the morgue allowed him to memorize the shapes and the parts of the human body. The corpses he saw ranged from those of young children to elderly individuals, practically mummified. During his stint in the military, San Juan took time from sleep –or standing guard– following strenuous days of training to draw pictures of bottles or skulls he found in the ossuary of the graveyard: skulls with hair, no teeth, of black and white people, dusty skeletons dressed in rags…

San Juan’s academic training is reflected in the large sculptures, drawings and unfinished structures done in classical style hanging from the walls of his studio, south of the city of Guadalajara. here, faces and torsos in large formats in ochre and sepia tones that could have been culled from a Renaissance mural are part of a malicious game: the artist attaches bits from wooden boxes, rags and ropes to these sensitive portraits as a comment on the shipping of packed art (fragile: handle with care) as merchandise exchanged between museums and galleries around the world, as well as the almost sanctimonious tone of reverence conferred on works of art.

At the entrance to the studio are stone, wood and reinforced cement sculptures, and from the ceiling hang large cocoons made from branches from which it appears monstrous chicks might burst out at any moment, when in reality dancers will emerge as part of a future performance work. Three enormous feet from those materials belong to the Éxodo series, which were created thinking of men, women and children who are forced to migrate from one part of the world to another for myriad reasons. One of those feet is pierced by spears, which will make the journey more painful. Also part of this series is that enormous wooden fish, with arms resembling ancient rowing oars protruding out from the ribs. The contemporary world does not allow an artist to work with the same phlegmatic nature employed by artists from other periods, says San Juan. Between trips, engagements and exhibitions, today’s artists are obliged to work with materials and resources that make their job a bit more difficult. he says this, but I look around and the pieces that I can see are all the product of patient and painstaking work. The tool shelves resemble those of the master of a mysterious trade. The sketch in bronze for a monumental sculpture that has not yet been finalized whose theme is the holocaust –which also provides the title for the piece– ; a pyramid-shaped heap of men and women helping each other to escape the horror, to freedom. The anatomy of the small bodies is perfect, as is also that of a triad of horses in another unfinished large-scale sculpture project. he is not worried about projects that have been left behind for one reason or another, as he has many more in mind. Nonetheless, he has the energy and the skill to work on more than one project at a time, as he did with large sculptures from tree trunks which were cut down ilegally in the Jalisco town of Tapalpa. Another indication of San Juan’s commitment to art and artists is the fundación Arte San Juan, which his former wife Alba Sahagún founded in 2007 to support young Cuban artists.

The Science of Art

The thinking of Rafael San Juan is closer to the reasoning of a scientist than to the romantic intuition that is generally thought to be associated with this endeavor –which is complex, indeed: art is also a form of activism, perhaps more discreet, but intense and persistent nonetheless. San Juan thinks, analyzes and reasons in accordance with the laws of logic and explains the genesis and each step of his projects with the eloquence of a lecturer and the passion of a poet. hailing from a small island, this artist has his feet planted firmly on the ground. he knows that art has a number of functions, which include understanding the world and trying to change it, difficult as it may be. his mature attitude with respect to art is a far cry from that of anachronistic romantics who believe art merely serves decorative or contemplative functions.

Several years ago, shortly after his arrival in Mexico, he saw enormous tree trunks which had been cut down by clandestine loggers near the mountain town of Tapalpa, in Jalisco. how could he transform those giant trees cut down by man’s predatory greed into proud symbols of strength, beauty and dignity? he worked with those gigantic pieces of wood, attaching ceramics and iron to them and turning them into the kind of sculptures that could be interpreted as millenarian symbols of sacred life similar to the grand totem poles constructed by American Indians. works of impressive solemnity that look on with inscrutable faces to the past and future, as a warning to modern man who is destroying the present with no consideration of the consequences. One of these huge logs is crowned by a circular saw that has a poem written on it with lettering also in concentric circles. Other logs have extended arms or boxes with human hands resting on a crossbeam.

A sculpture without social conscience has very little use, according to San Juan. This dramatic series, Orígenes –which Rafael also refers to as the Fallen Giants –has its origins in the grief and the need to redress nature and return something to it, which is why part of the project involved planting thousands of trees in the area together with residents of the community. Trees killed by greed but which came back in the name of tolerance and survival, not only of their species but for all life on Earth. This is one of the ideas that govern San Juan’s artistic endeavors and sets him apart from those who find a peaceful way of life in art.

The life of an artist goes through unpredictable cycles. San Juan is going through one such cycle in Mexico, where he arrived as part of the Cuban delegation that created the colorful pavilion for Cuba’s International Book fair 2002. In Cuba he had learned to be an artist and work as a set designer with theater and dance companies. More recently, he has had the opportunity to develop other facets in a country with many similarities to his own, but also profound differences.

Some works by San Juan such as the big hearts and faces with frameworks of sticks and clay reminded me of another Cuban artist, Juan francisco Elso (1956-1988). Such works reflect the common sensibility of recent Cuban art that is also been nourished by ancestral cosmogony, visions rendered from an understanding and contemporary perspective. I believe that San Juan’s sculptures go even beyond that, since he incorporates materials and elements which charge them with disturbing codes and meanings: fragmented bodies, threatening iron wheels, brains. Such images stir thoughts of death, desperation and resistance, but also of sensuality, eroticism and the beginning of life. A refined black humor also runs through much of his work, such as the one with men of stone sitting face to face and joined at the stomach by a large glass box with viscera (Escenas de mesa). Powerful pieces which inspire reflection rather than contemplation, built with a language that is both profane and sacred, and that demand a skeptical, pagan interpretation. López Oliva was right when he said that San Juan lacks «the anti-classic, anti-figurative» or «anthropocentric prejudices –which are so frequent in the artistic conscience of young contemporary Cubans» and among the majority of artists in the world today. That has been his great success, since as a member of a lineage that goes back to the beginnings of humankind, San Juan has had no qualms with drawing on every resource available to him from the history of art and artists and also from technology and the knowledge of those materials best suited to his expressive needs. So his works can be seen as a natural continuation of classic and Renaissance art while also seeming so contemporary with their myths, demons, angels (which do exist), tragedies and uncommon happiness: a steely-eyed reflection not only on our time, but of our fragile condition.

This brings us back to the initial ideas expressed here: beyond the debate between conceptualism and traditional art, artists such as Rafael San Juan transcend an artificial situation –which they have never experienced– and situate themselves in the most noble and useful plane of art, that which appeals to human nature and nourishes the mind and spirit; an art that proposes changes, actions, in the lives of men and women –even if only imperceptible ones. Another work, to which he keeps going back recurrently made up of tens of fist-sized ceramic hearts, each different, has been disseminated in as many houses of San Juan’s friends and acquaintances, who have placed them in their living rooms, cupboards and bedrooms, and have given them the most varied uses. These hearts are elements capable of altering everyday life and inspiring unique ideas and actions. Seeing a heart that could be ours is like looking into the mirror of one’s soul.

The amazement that the work of San Juan evokes stems from the vast richness of his ideas and his precision. (how can we not smile dismissively when we hear people like filmmaker Bruce LaBruce say, «Intellectual property is theft»?) works made of flesh, steel, wood and stone: the world’s material: life and earth. The anguish and hope invested in art that are also a compendium of human history and universal art. If only some parts of the work of San Juan were to remain at the end of time, those pieces would bear painful witness to a civilization that was close to attaining peace and harmony, but chose the path to destruction. (Testimonials peppered –we have already mentioned it– with much-needed black humor.) Rafael San Juan works to prevent that moment from ever coming.