DEATH

OF A

PROJECT

EACH ONE IN A NATURAL ATTITUDE,

AS IF THE ABSENCE OF FLESH

WOULD NOT HAVE IMPAIRED IN THE

LEAST THEIR INTELLECTUAL

CAPACITY OR WILLPOWER. ANY OF

THEM COULD, HAD THEY INTENDED

TO, ABANDON THE HALL AND

CONTINUE THEIR WAY ELSEWHERE

RAFAEL SAN JUAN

Throughout the history of humankind, life and death have formed the emblematic couple par excellence. Based on the most dissimilar premises (religious, philosophical, ethnologic, medical, artistic), numberless beliefs or convictions have been generated that accompany human existence from their particular points of view. Being on one side or the other, generating infinite certainties or apprehensions, the truth is that it is impossible to pretend not to take into consideration the specific and general connotations that this dichotomy presupposes even in our days.

Neither the ever more surprising scientific advances nor the huge socialization of the access to information entailed by the new technologies have succeeded in homologating, and much less in standardizing our notions on life and death. Like an endless song, equivocal and ancestral, it thunders or whispers; and each individual is bearer in himself of a unique score that he later interprets as he can or wishes to.

To Rafael San Juan these have been recurrent obsessions, revisited over and over again. The artist has found in the very substance of this dichotomy an infinite toolkit for his work: the human body. In an impulse that is closer to Thanatos than to Eros, his proposals however tend towards a sort of aestheticism or sublimation of the human essence, particularly when inert and died out, it becomes a cardinal piece, a primitive element.

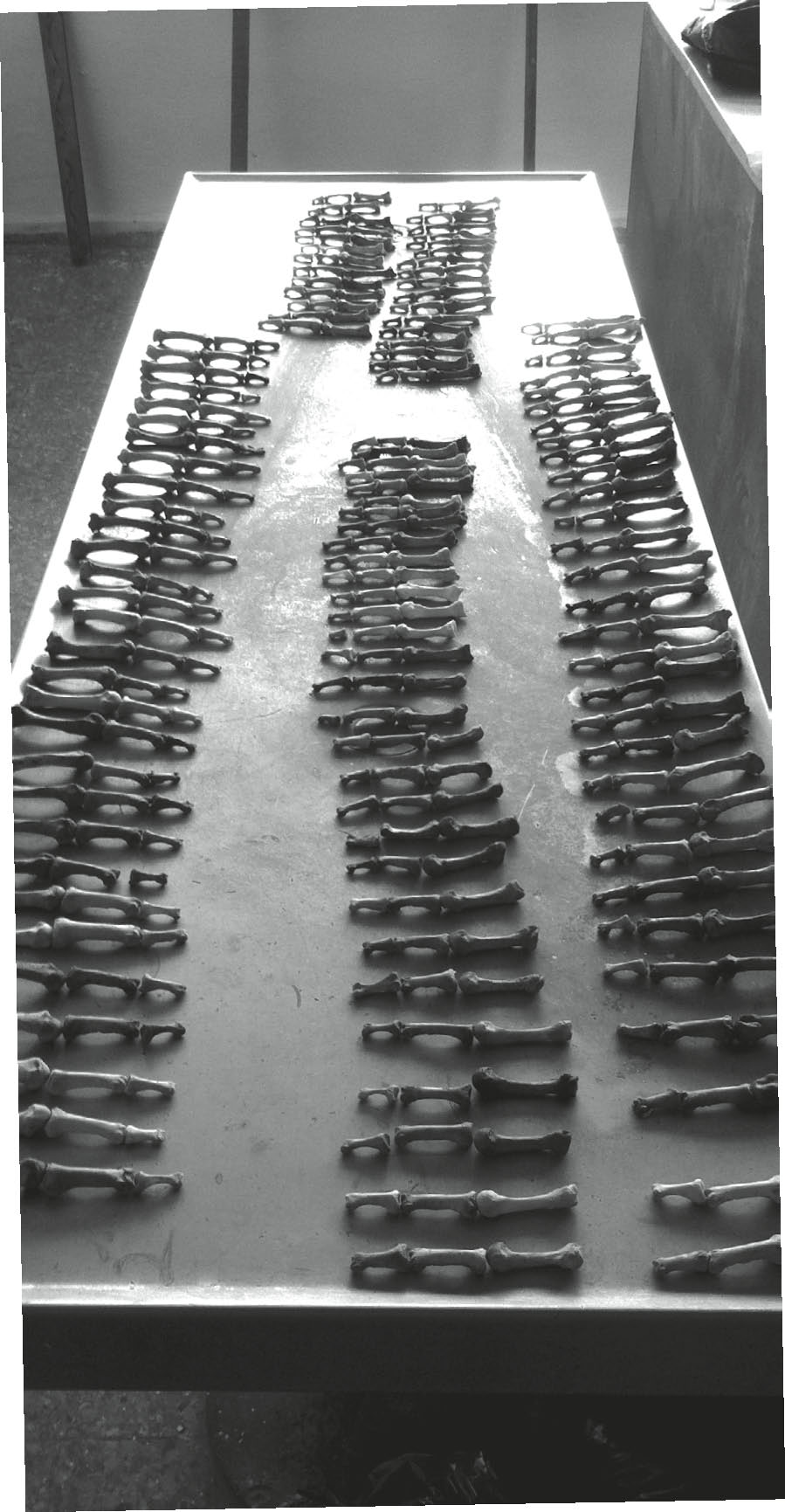

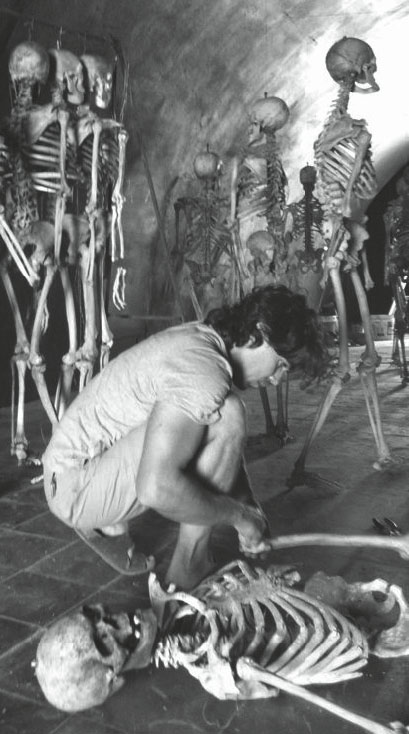

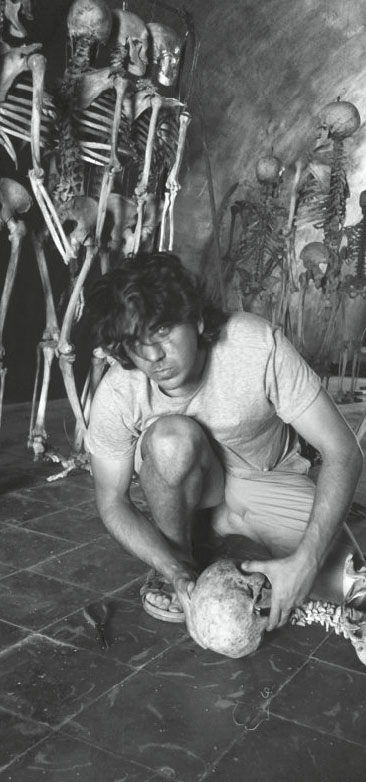

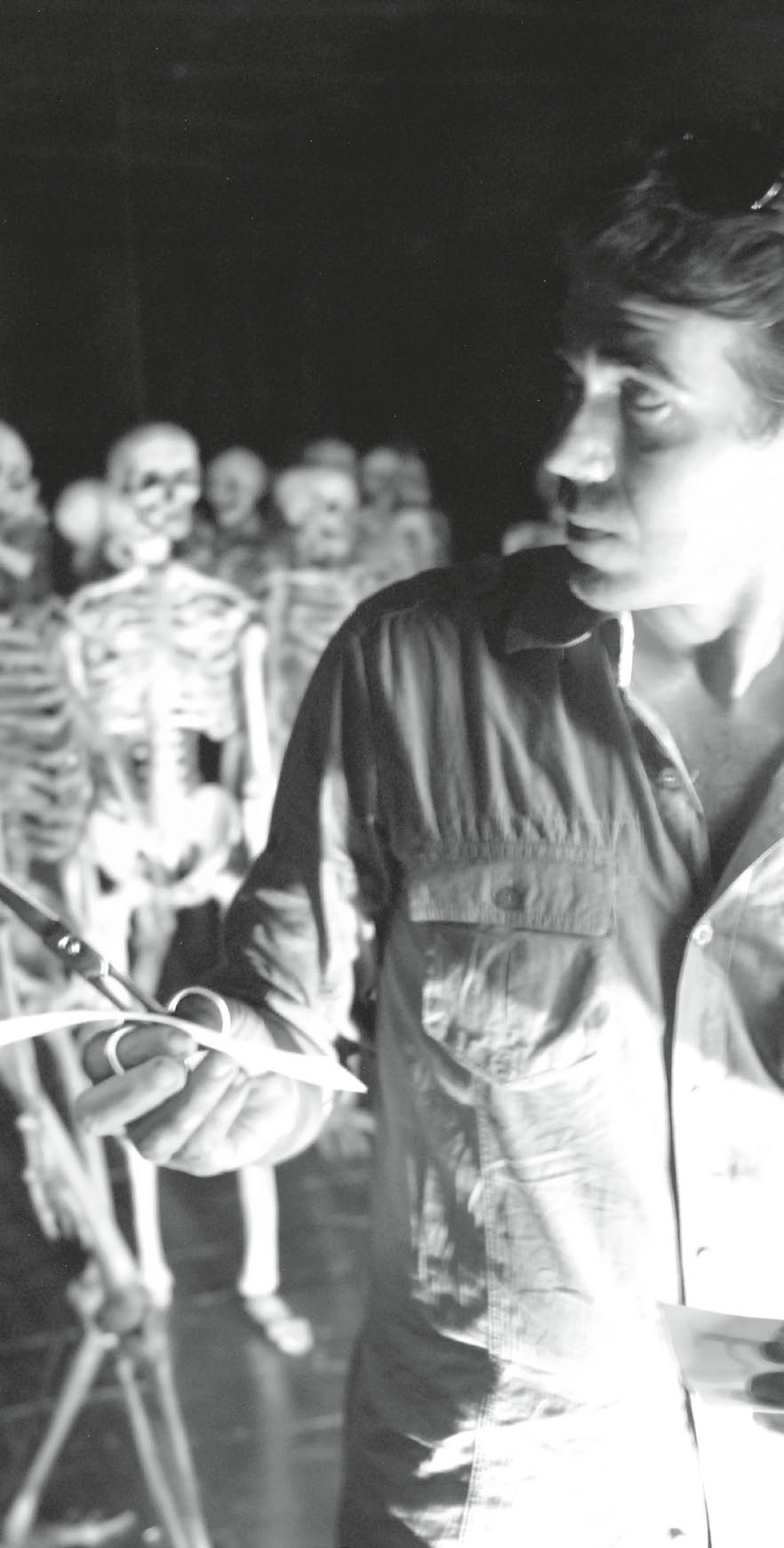

For the eleventh edition of the Havana Biennial (2012), San Juan sketched, projected, conceived and created a number of large format sculptures under the generic name of Los caminantes (The Walkers). It was an ambitious project that attempted to set up around ninety nine pieces made in the most dissimilar materials in some semi-public space of the exhibition circuit. But the circumstances, the budgets, or perhaps the stars decided to tense the rope, and the artist was forced to present his proposals from a different point of view.

«Certainly, the starting point was Los caminantes, and from there emerged La muerte de un proyecto, (Death of a Project) using the idea of the material as bearer of a content par excellence. When I began to build these forms and create the piece, I started in parallel a personal research and many things came to my mind. It was a material that I did not produce or take, but that the human being, throughout his life, throughout the process of growing up and educating himself, gradually enhanced with prints, marks, testimonies of multiple experiences that accumulated until he died.»1

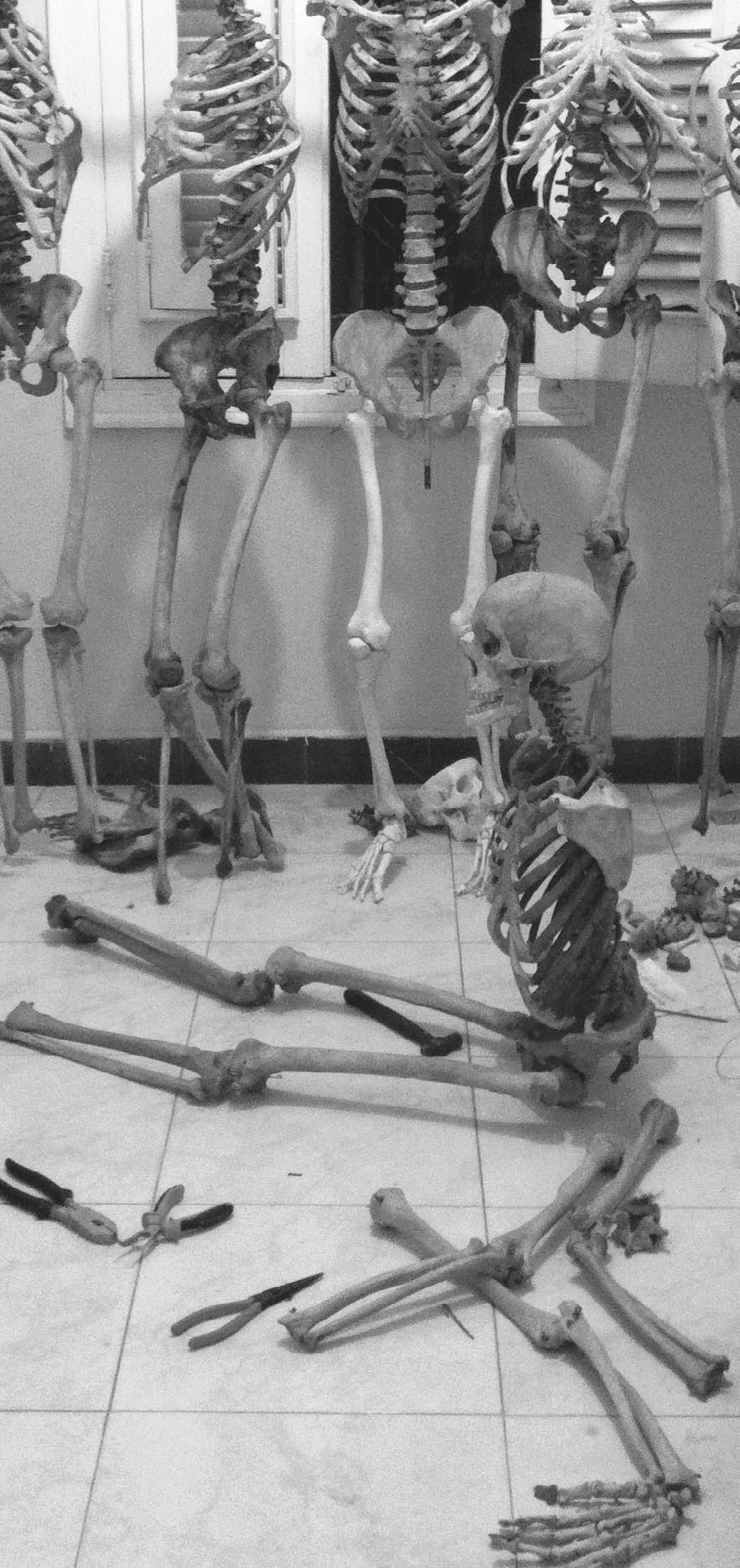

It should be clarified. In the face of the unconquerable inconveniences faced by San Juan for the timely production of his «walkers», it was scarcely probable that a reorientation could take place, particularly when the main part of his work involves sculptures at ever more monumental scale or large and extremely complex installations. There was an initial moment when the project seemed to be sentenced to a fatal outcome. But the metaphor of this imminent death, next to the artist’s irrefutable genius, favored the achievement of a strategy articulated from the deepest levels of significance. Now his walkers would be deprived of all gadgets. Simple skeletons would invade on of the vaults of San Carlos de La Cabaña and skeptical, slightly protected from the elements, would tackle the common walker, the casual or trained spectator, making him face the show of an inevitable reflection: the value of human existence.

«The purpose was to express the essence of a human being glancing at the human being. I was proposing to stop off and find ourselves. I proposed it as a solemn act toward humankind.»

It was overwhelming to undertake the odyssey of touring the hall. Dozens of skeletons awaited you. They were strange to any instructive attitude that we could infer as reference to a probable Final Judgment; neither did they seem to be in the festive attitude of All Souls’ Day. They simply were there: seductively hieratic and indifferent. Each one in a natural attitude, as if the absence of flesh would not have impaired in the least their intellectual capacity or willpower. Any of them could, had they intended to, abandon the hall and continue their way elsewhere.

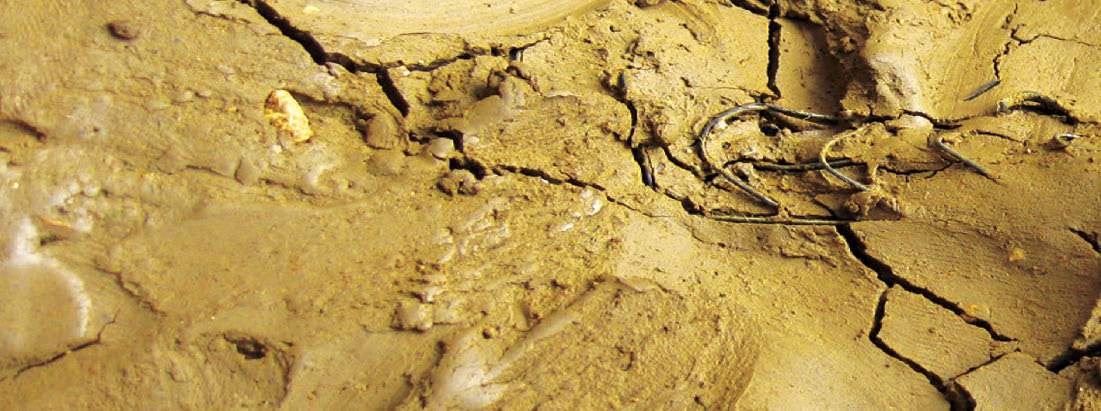

«That testimony, that expression of the faces, of the bones – some even still had steel fasteners – were beginning to show signs of what each individual could have been. From then on it became an independent piece with its characteristics and peculiarities.» However, the evident connection between them multiplied and expanded the possible readings, leading us deeper into an infinite bundle of reflections and considerations. Each individual who would cross the threshold and go inside the hall could face his own feelings, fears, affections, afflictions, hopes. With very little probability would he escape the sudden shock, even a kind of embarrassment connected with the atavistic defenselessness of humankind in the face of the unknown. Past, present and future melted into a reflection anchored on the very substrate of life, in the most elementary and primitive of existence.

«It was easy to maintain that dialogue with the pieces, find them, classify them, organize them and finally place them. The material resulted very warm, even though they were bones, corpses. I did not have the least apprehension. In all the cases they were anonymous persons, the great majority of them from medicine schools where they had been more than twenty years in crates and caverns, mixed, in disorder…» This detail could have contributed to underline the perception of attendance, of adding. Because in spite of the fact that when reassembling the bones the artist very probably mixed the donors, he also gave them back certain dignity, elegance, beauty, strengthened by the very fact of acting as a group. He inserted shreds of an epic, intimate chronicle, mixing and reinventing stories told, dreamt or lived one thousand times. San Juan thus proposed a narrative where art, history, creed, reconfigured the mapping established in accordance with the new physical associations of his characters.

La muerte de un proyecto thus seen, is a great installation that could extend to the infinite its connotative pretensions, since, paraphrasing García Márquez, death does not arrive with old age, but with oblivion. And then, only it stones the lack of memory and marginalization. That «change of mission» of Tolstoi’s that approached with death presupposes only one challenge: the commitment to sustain the future.

1 All quotations belong to an interview with the artist, made by the author in late 2012.

* Bayamo, 1968

Chief editor of ArteCubano Ediciones. Editor, art critic and curator. Curator of the collection of the National Council for the Visual Arts. Prize in Curatorship in 2011.