WALKERS

THAT ATTEMPT TO CONTEND WITH

ELEMENTS OF LIFE ITSELF AND

WHICH TRY TO REPROACH AT ALL

COSTS THEIR SENSE OF

TRANSCENDENCE AND PERPETUITY

RAFAEL SAN JUAN

Ceramic sculpture of small and medium format was the last resource, the first-hand alternative to reactivate Cuban sculpture in the early nineties. It served to overcome the hazardous inconvenience of negligence, of the creative impasse that comprised equally all art forms toward the end of the eighties and beginning of the nineties, and to compensate the profound crisis of resources it endured, showing a possibility of pursuing certain ideas and projects.

Although sculpture was one of the last expressions to give signs of revival (first came painting, engraving, photography and design), it entered a process of formal and allegorical reevaluation that is still showing its best results. The renewed setting in a context of esthetical canons and historical symbols of representation; the recovery of technical tricks or gadgets (what others called the «return to the craft»); the simulative and at times «perverse» renewed adaptation to notions related to the classic or academic style, the rescue of the figurative trend and the repositioning of the human body were some of the forms through which the modifications were channeled in the field of third dimension.

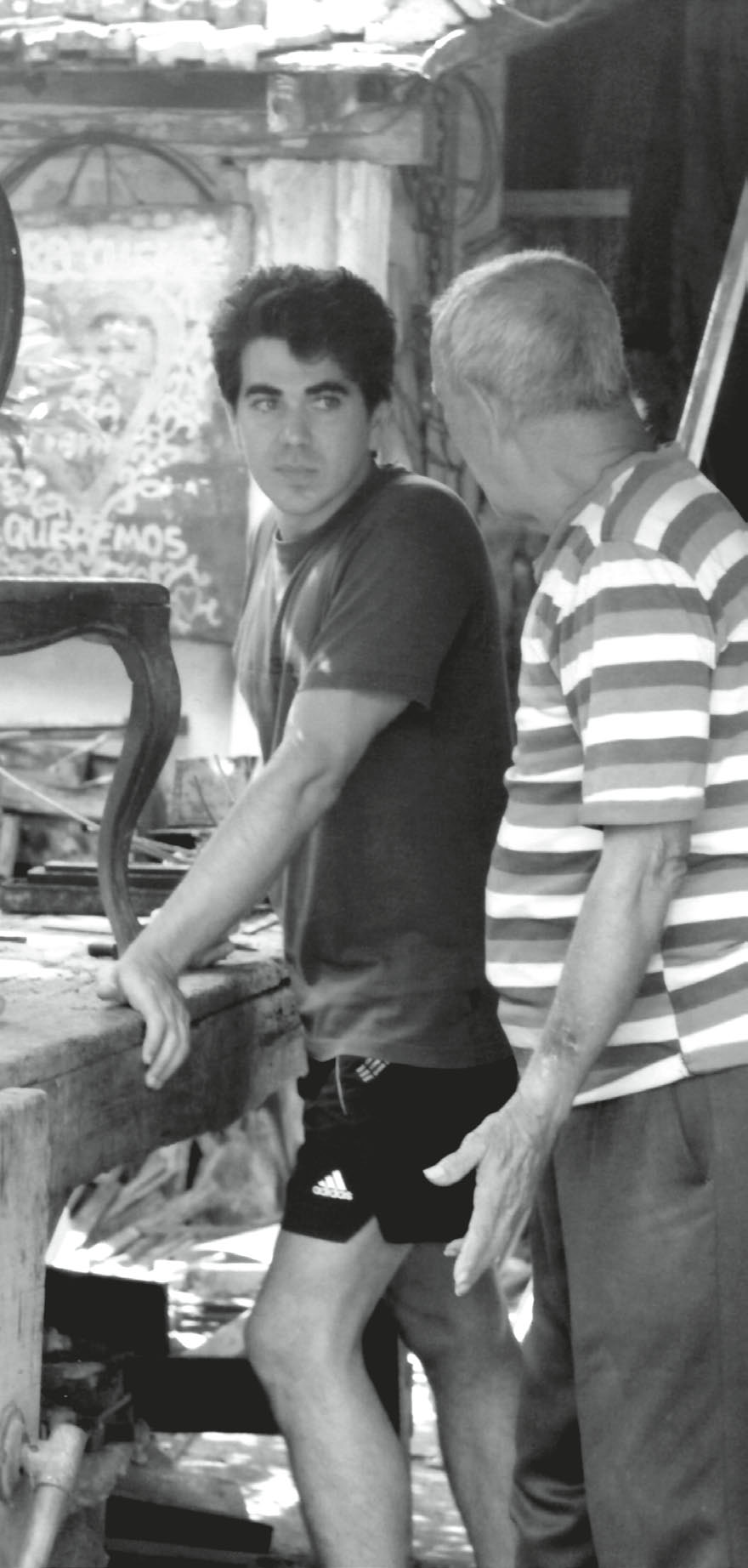

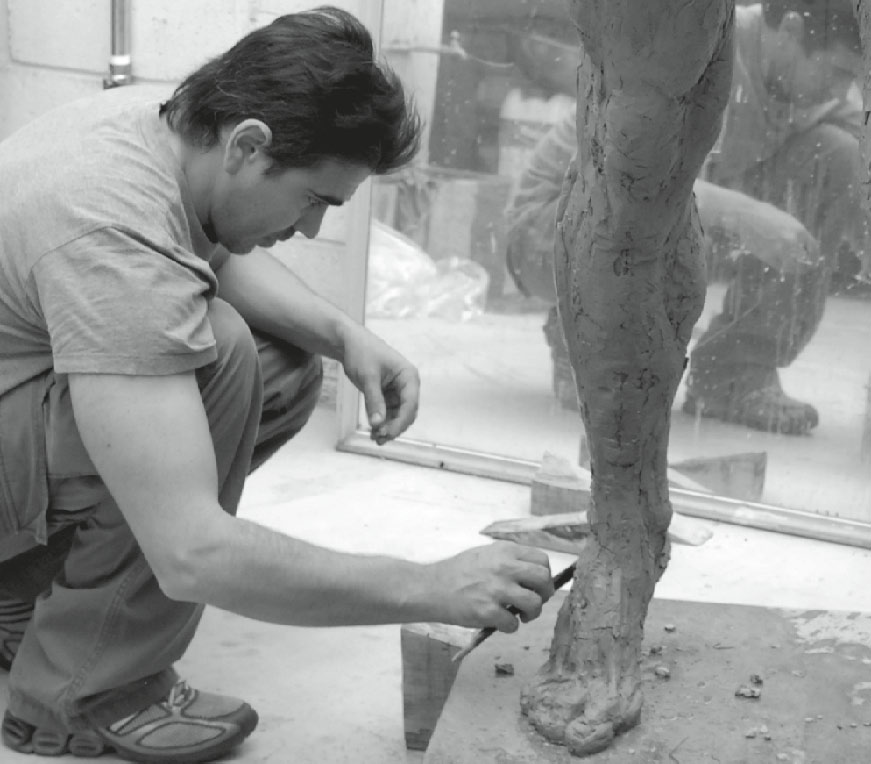

The work of sculptor Rafael Miranda San Juan has lived through those circumstances and has been imbued with those art premises. A review of his production along these ten years evidences that the work of ceramic sculpture has been at the base of his evolution and perfection as a creator. The essence of his eagerness to experiment with other materials, dimensions and supports lies in the dominion he has been gaining of volumetric forms, in the power of synthesis he has been capable of attaining, in the subversion of themes and expressions to which ceramics has been conjuring him. It is possible that such a testing will was revealed early, when he had just finished his studies at San Alejandro Academy, but it was ceramics that pointed the way of its practical implementation.

Toward the mid-nineties I was able to verify for the first time his ability to manipulate ceramic relieves in a group of works he exhibited at the Provincial Center for the Visual Arts and Design, some of which I think I saw years later in a Salon on eroticist art held in Havana in early 2000. Those pieces belonged to the series Beyond Closed Doors, and were loaded with strong eroticism, of a shamelessness bordering on commiseration. With them, Rafael succeeded in taking over the attention

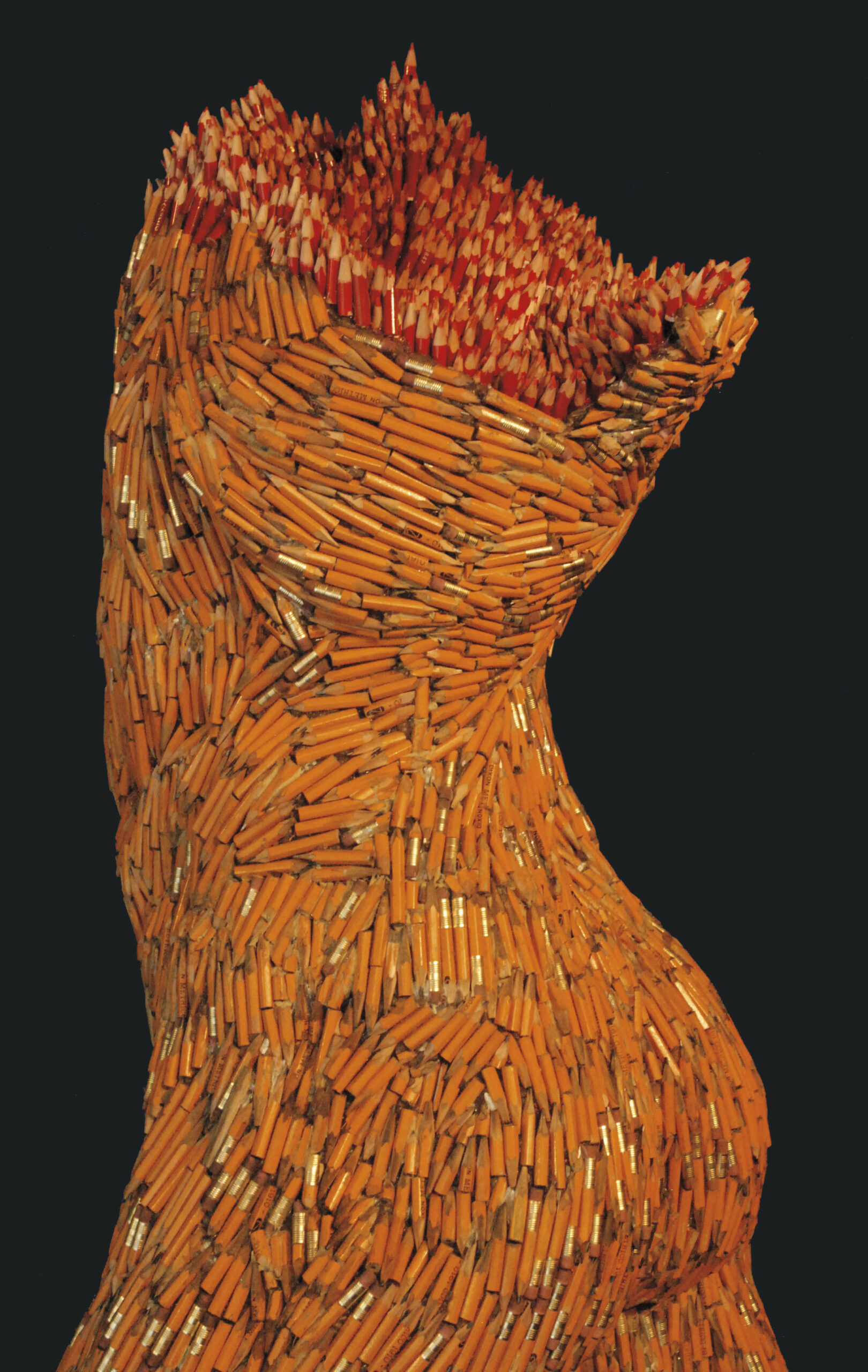

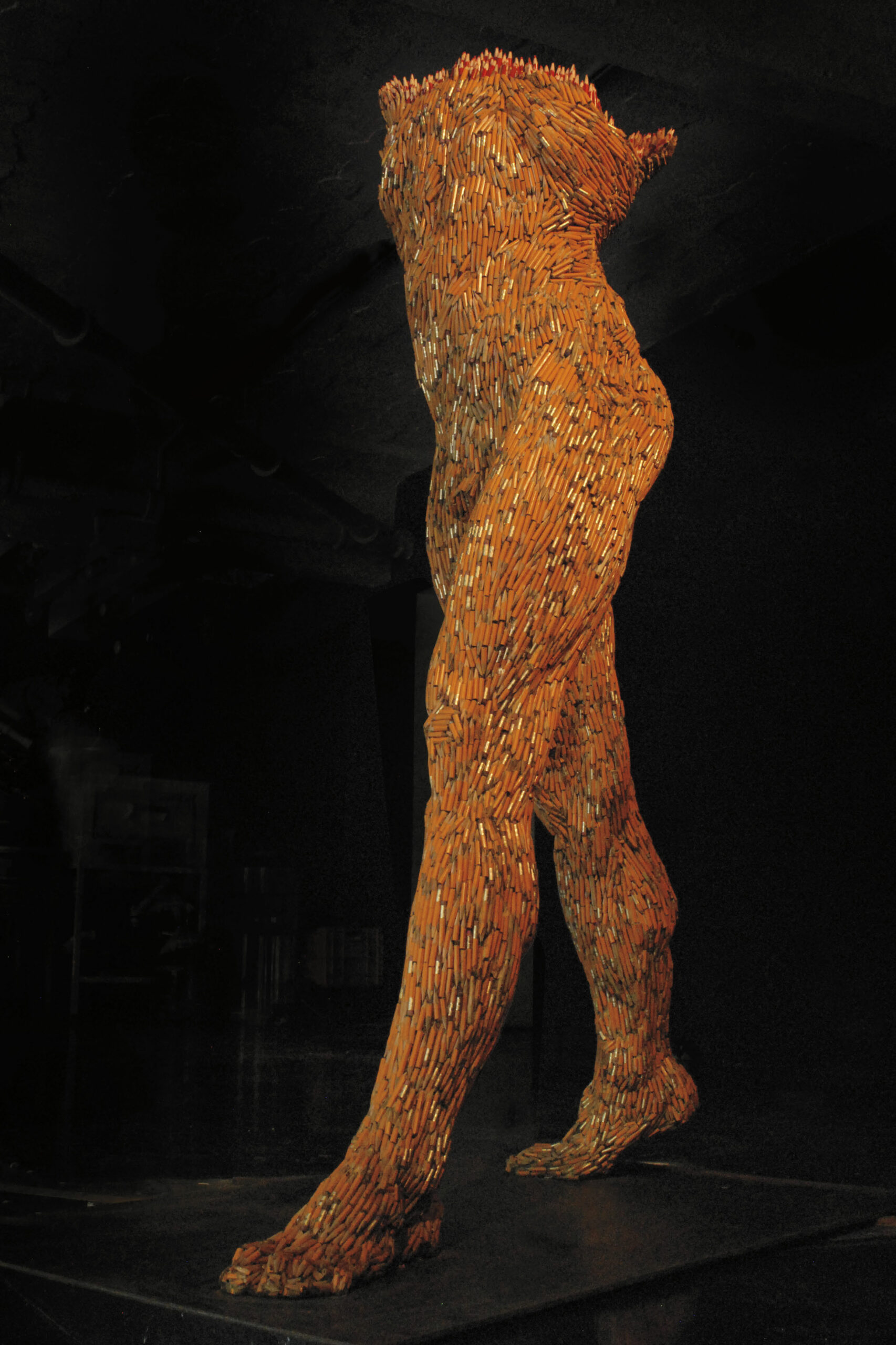

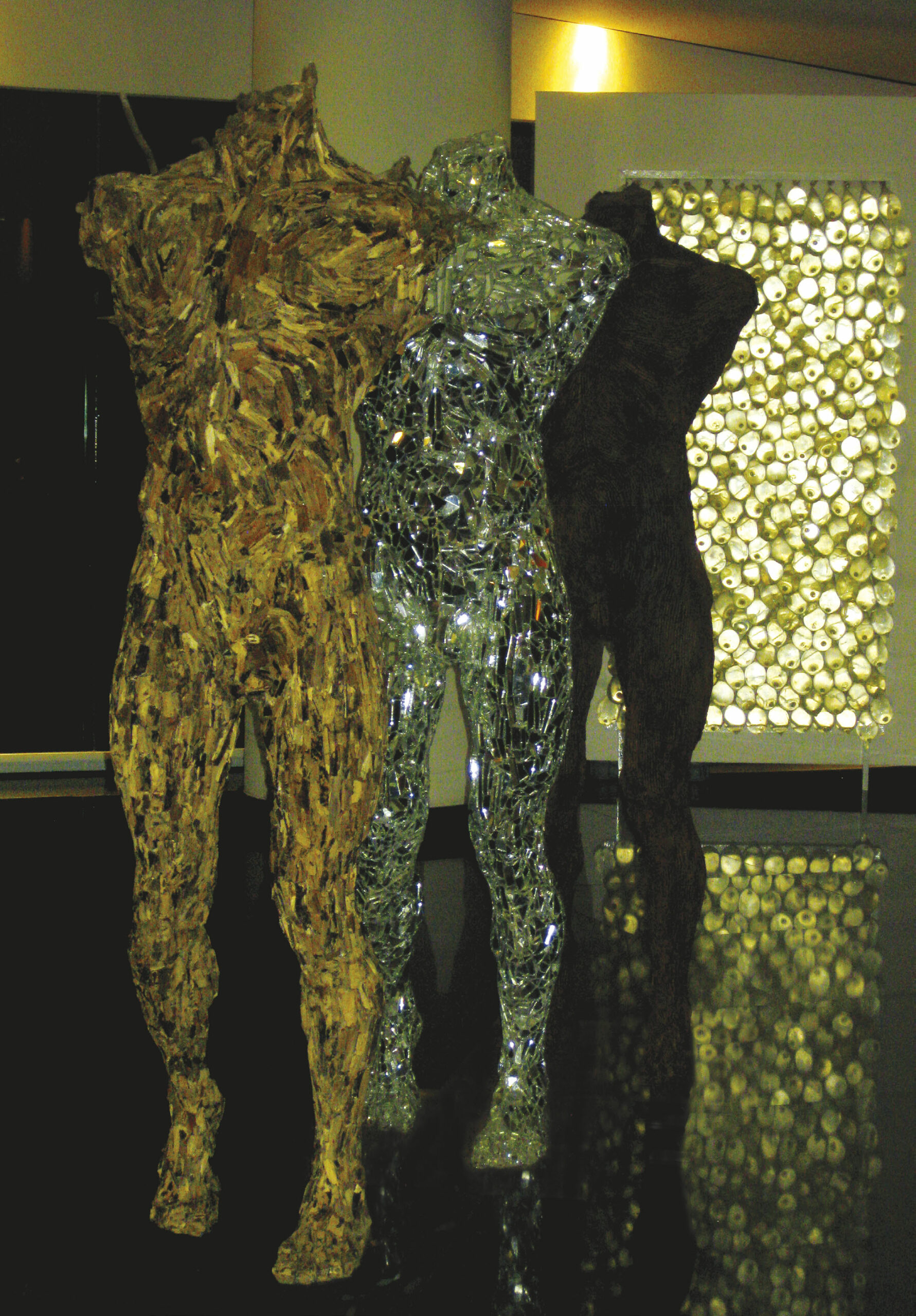

of artists and specialists from the art circles and established impeccable evidence of his qualities as a sculptor. In 2000 I visited another of his exhibitions, a truly far-reaching one, in the National Museum of Ceramics, the institution that dared recognize the work of renewing artists within the ceramic sculpture of that period. I remember the magnificent human figures sculpted by Rafael Miranda for that occasion, the sensuality and suggestive force of the feminine torsos, the expressiveness of the mutilated and pierced bodies, depositaries of highly complicated effects and ceramic wefts, the interesting contras propitiated by their composition and textures in the somber atmosphere of the place and the creased walls of the Castillo de la Fuerza fortress.

A work that appears to me also as representative of that correspondence in evolution and premonition established by San Juan with ceramic sculpture is the altarpiece The History of Time, the Time of History, which I recently had the opportunity to appreciate by courtesy of the artist. Although it is a foundational piece from 1996, one may discover in it the conceptual and technical abilities he had at an early period, and above all, to deduct the level of prerogatives, the plurality of compositional variables that his work was to achieve later on.

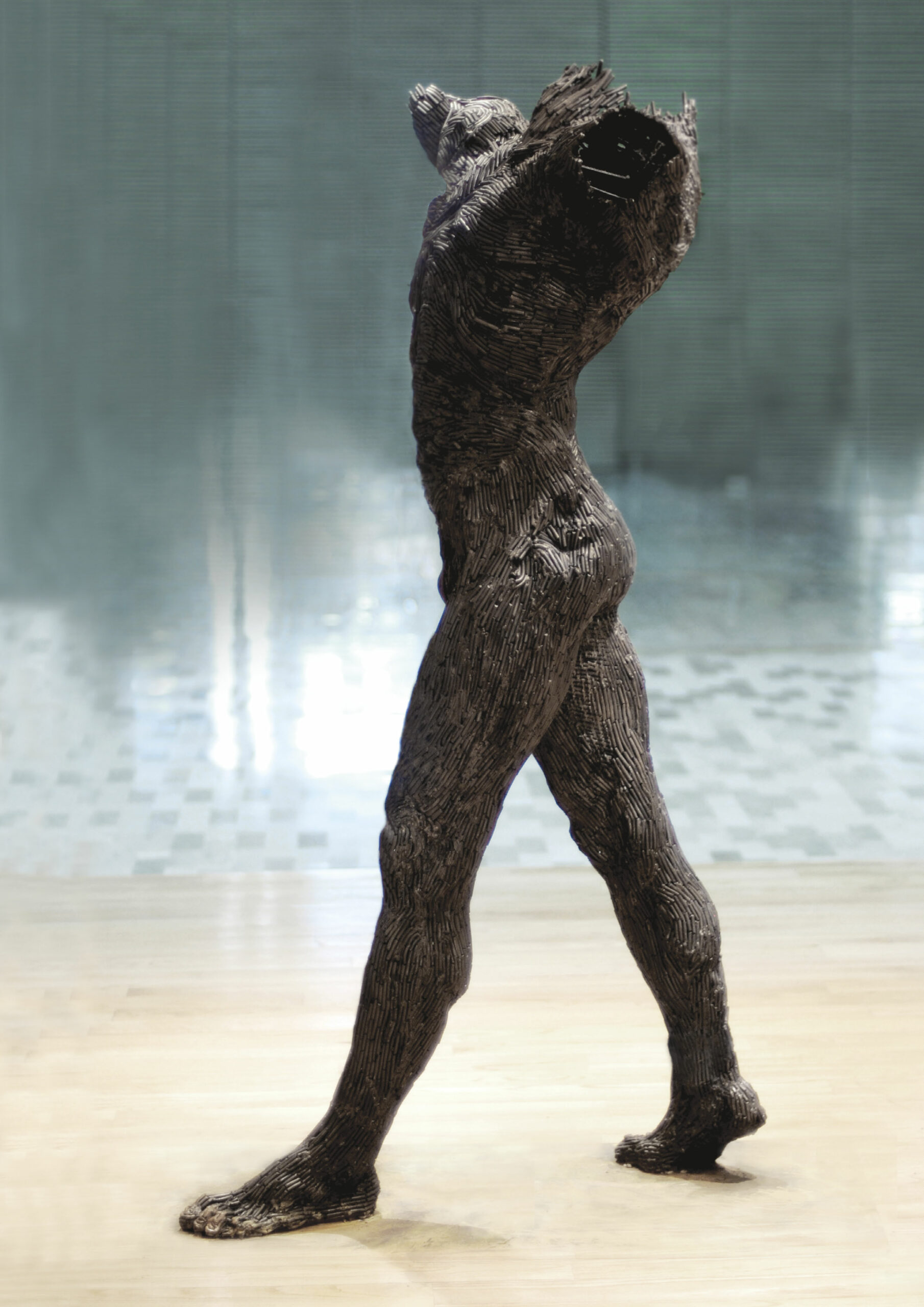

The fact that Rafael Miranda has been alternating for some time now with other materials such as wood, steel or bronze –even deeply involved at times in the elaboration of some grotesque, disturbing, rustic sculptures (Dialog, 2006, Matrix 003, 2010)– may be understood, in my opinion, as originated by two main causes. One has a circumstantial nature and not only applies to him but to a good many sculptors of his generation; the other is essentially creative, of authorial nature, although I think his pieces attain greater effectiveness when these materials are combined with ceramics. To me, the sculptures of the exhibition Origins (2005-2006) are emblematic in that regard; they are among the best he has created along his career.

The moment in which installation and sculpture in Cuba required the efficacy of a formal and esthetic seduction to surpass the apparently immovable standards, the canons of appreciation of previous periods, and strive to recover promotional spaces and new spectators in Cuba and abroad has been left behind. Now that conceptual art is in a phase perhaps less determinant and mediatory, now that it enjoys a little more autonomy and solvency, not only is he determined to be more inclusive, daring, willing to extend to the utmost the expectations of his technical procedures and allegorical strategies, but has dared recycle –not without mistrust– certain methodological notions and perspectives accredited at times when he thought he was more sufficient: the decade of the eighties. How could we possibly have questioned the fire-raiser potentialities of the old ashes? At least I am not taken by surprise when someone now, in good faith, attempts to relate some of Miranda’s sculptural proposals with those of paradigmatic Elso Padilla, as I recently read in an article dedicated to his work. More than dead weight, I am certain that to him, that suggestion of connection must be quite flattering.

No less true is also the fact that ceramic sculpture still has among its basic essentials a technicality and a dimension of esthetics that might at a certain point attempt against the solidity and strength in the enunciation of certain discourses, all the more in the case of sculptures like Rafael Miranda’s, strongly based on histrionics and drama, which turn out to be non-conformist, disturbing from their own physical achievement; that attempt to contend with elements of life itself and which try to reproach at all costs their sense of transcendence and perpetuity.

* Matanzas, 1965

Journalist, art critic, curator and editor. he received the Guy Pérez Cisneros

Prize in Critique in 2002 and the Prize in Curatorship in 2001.

resident of The AICA Cuba Section.